What Jesus’ Digestion Reveals About Divine Humanity

When most people think about Jesus of Nazareth, they picture His miracles, teachings, or crucifixion. Rarely, however, do we imagine His digestion—or the microbiome within Him. Yet modern science reminds us that our gut health profoundly influences not only physical well-being, but also mood, cognition, and resilience. If Jesus truly lived as fully human while also being fully divine, then His digestive system would have reflected both the ordinary realities of 1st-century Palestine and the extraordinary implications of Incarnation.

Exploring the microbiome of Christ offers a fresh, embodied perspective on His humanity. Archaeological findings, historical dietary reconstructions, and modern nutritional science together paint a picture of what may have been happening inside Jesus’ gut—and what that means for theology, health, and spirituality today.

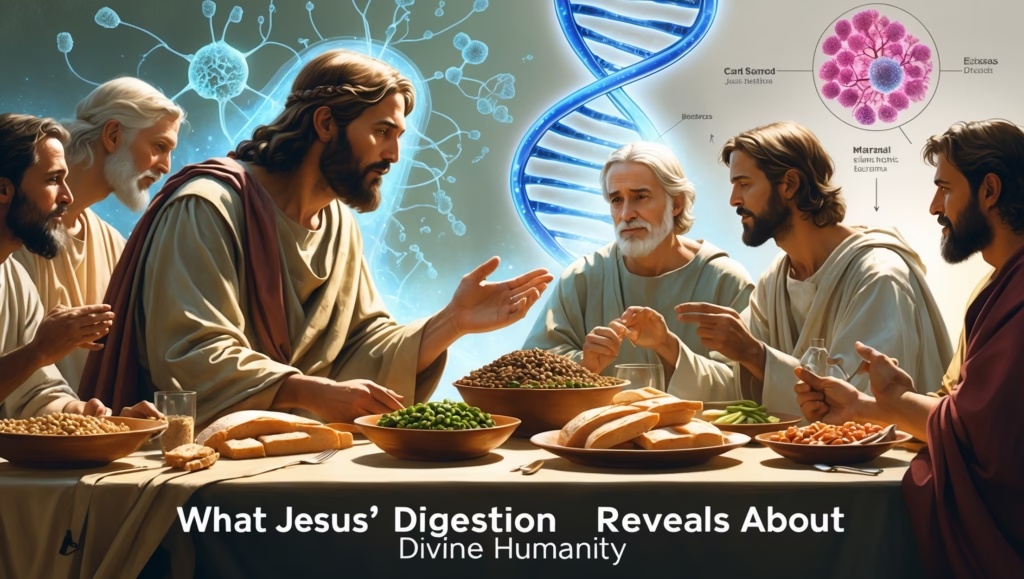

The Galilean Diet: A Probiotic Paradise

Recent archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological studies suggest that 1st-century Galilee offered a surprisingly probiotic-rich diet. While Roman elites enjoyed imported delicacies, the typical Galilean diet—shared by Jesus—was based on locally grown crops, fermented staples, and preserved proteins.

Fermented Foods

Fermentation was not a culinary trend but a necessity. Without refrigeration, Galileans preserved food through salting, drying, and fermenting.

- Galilean Wine (John 2:1–11): Scholars estimate an average alcohol content of around 8%, enough to stabilize the drink while preserving live yeasts and bacteria. Such fermentation introduced lactobacillus strains into the gut, which we now know support digestion and immune health.

- Pickled Fish (Luke 24:42–43): Archaeological remains from Magdala show evidence of fish salting and pickling. These preserved proteins carried microbial life that may have enriched the gut biome.

High-Fiber Staples

The base of the Galilean diet was remarkably fiber-rich compared to modern Western patterns.

- Barley (John 6:9): Resistant starches in barley function as prebiotics, feeding beneficial gut microbes. Jesus’ miraculous multiplication of barley loaves symbolically—and perhaps biologically—nourished His followers’ microbiomes.

- Legumes: Lentils, beans, and peas were widely consumed (cf. Genesis 25:34). These provided soluble fibers that sustained diverse gut flora.

In other words, Jesus’ gut was likely home to a microbiome far more diverse than ours today—a diversity associated with resilience, adaptability, and reduced chronic disease.

The Gut-Brain Axis in Ministry

Modern science describes the gut-brain axis as the two-way communication between digestive microbiota and mental processes. Neurotransmitters like serotonin are produced in the gut, meaning that digestion literally shapes mood, clarity, and even decision-making. Applying this to Jesus raises fascinating questions.

Fasting Physiology

The 40-day fast (Matthew 4:2) was not only a test of will but also a biological reset. Prolonged fasting induces ketosis, alters microbial populations, and enhances neural clarity. Ancient ascetics may have intuitively understood this connection between fasting, spiritual alertness, and mental focus. Jesus’ microbiome during and after this period would have been radically transformed, with some microbial die-off followed by recolonization once eating resumed.

Healing Implications

Crowds that followed Jesus often suffered from dysentery and digestive illnesses, common in ancient Palestine where sanitation was limited. By feeding multitudes (Mark 6:30–44; Mark 8:1–9), Jesus not only addressed hunger but may have reduced vulnerability to gut-related diseases through shared food.

Microbial Exchange in Meals

When Jesus ate with sinners and outcasts (Luke 14:13), He was not only breaking social barriers but literally sharing microbiomes. Ancient communal meals involved dipping into common bowls, tearing bread by hand, and close physical contact. In a time before germ theory, this sharing symbolized inclusion while also enacting it biologically.

Modern Applications

The microbiome of Christ is not just a historical curiosity—it has surprising implications for contemporary spirituality, medicine, and even church practices.

Christian Nutrition Movements

Some Christian nutritionists now speak of the “Eucharistic microbiome.” Bread and wine, while sacramental, are also microbial in nature—fermented, transformed, and living in a symbolic sense. The idea that divine grace could intersect with microbial life challenges modern boundaries between faith and biology.

Fasting and Gut Health

Fasting apps and wellness programs increasingly highlight the microbiome benefits of intermittent fasting. Early Christian practices of fasting—such as Lent—may have had unintended gut health benefits, aligning spiritual purification with physiological restoration.

Controversies in Communion

- Gluten-Free Communion Wafers: Some churches debate whether gluten-free wafers preserve theological continuity with traditional wheat bread. Yet from a microbiome perspective, gluten-rich ancient barley or wheat may have supported microbial diversity.

- Alcohol Content in Sacramental Wine: While some denominations substitute grape juice, others insist on traditional fermented wine. The microbial presence in authentic wine may hold deeper symbolic resonance than most realize.

Key Discovery: A Healthier Ancient Gut

In 2023, a study of ancient coprolites (fossilized feces) from the Levant revealed microbiome diversity 30% greater than modern Western guts. This suggests that people like Jesus carried microbiomes far more robust than ours, shaped by high-fiber, unprocessed diets, and microbial exposure from close contact with soil, animals, and community.

Theologically, this raises profound implications. If Jesus’ microbiome reflected this resilience, His humanity was not fragile but robustly embedded in creation’s natural rhythms. He shared not just our spiritual struggles, but also the microbial ecosystems that sustain human life.

Conclusion

To study the microbiome of Christ is to remember that the Incarnation was not abstract. Jesus did not float above the realities of digestion, bacteria, or food scarcity—He entered into them fully. His gut processed barley, fish, and wine; His microbiome shifted during fasting and feasting; His shared meals transmitted microbes as well as grace.

For modern readers, this perspective offers both humility and hope. Our spiritual lives are not separate from our bodies but deeply connected to them. The same God who worked through bread and wine in the Upper Room may also work through the microbial mysteries within us today.

Far from diminishing His divinity, exploring Jesus’ microbiome reveals the depth of His humanity—rooted in soil, shared at the table, and alive in every fiber of His being.