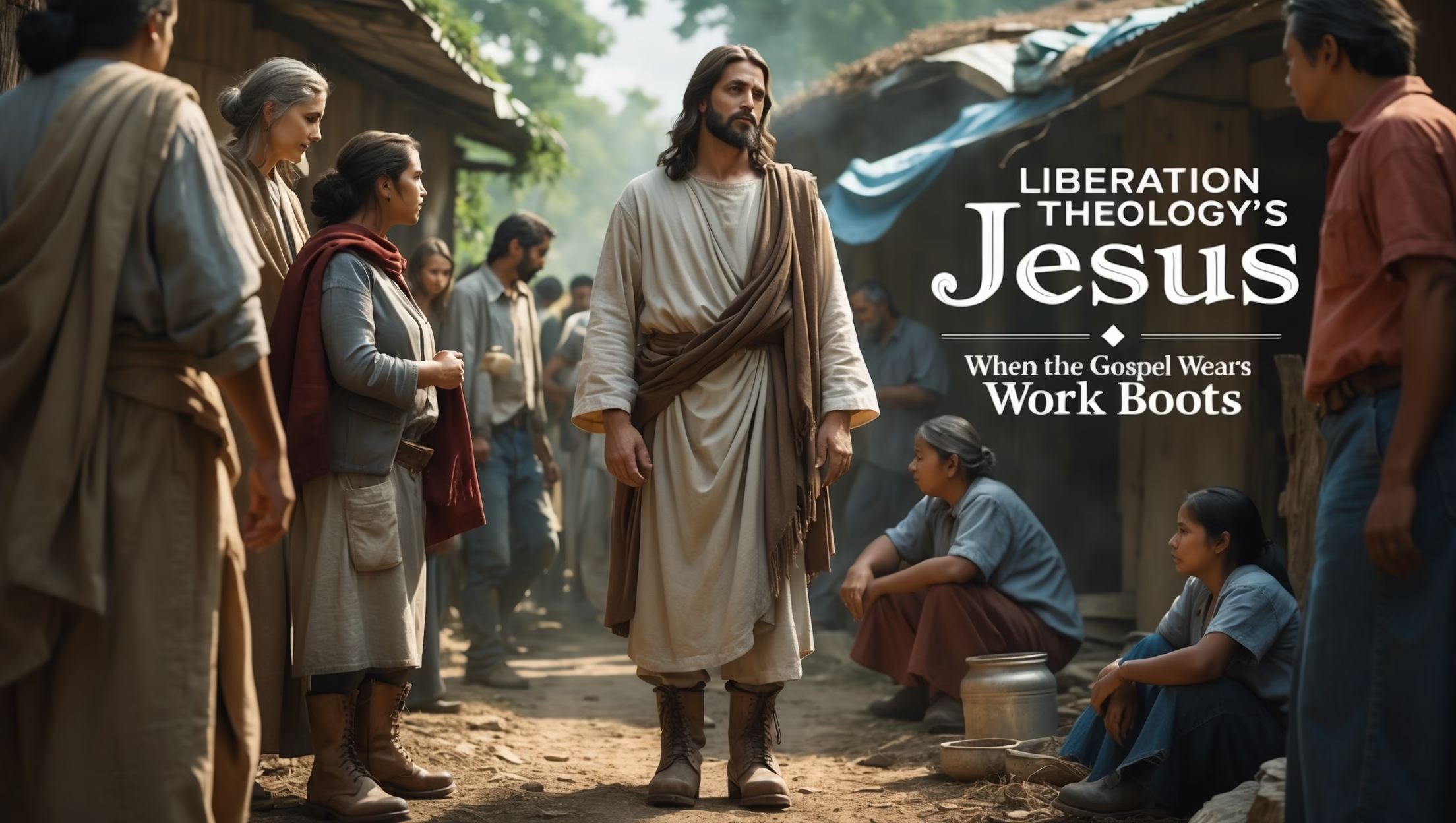

Jesus Christ has inspired countless theological reflections, but few have been as politically and socially engaged as Liberation Theology. Emerging in Latin America during the 1960s and 1970s, this movement reads the Gospel through the lens of poverty, oppression, and systemic injustice, portraying Jesus not only as Savior of souls but as a champion of the marginalized and downtrodden. Liberation theologians argue that the Gospel demands concrete action in the real world—challenging structures of economic and social inequality while remaining firmly rooted in Scripture.

The Historical Context

Latin America in the mid-20th century was marked by stark economic inequality, political repression, and social marginalization. Large populations lived in slums or rural poverty, often excluded from political and economic participation. Against this backdrop:

- Catholic clergy and laity began interpreting Scripture in ways that spoke directly to the suffering of the poor, rather than abstract doctrinal formulations.

- Base communities (comunidades eclesiales de base) emerged, small grassroots groups that combined Bible study with social activism, reflecting the belief that faith must engage with real-life oppression.

- The movement blended traditional Catholic teaching with insights from social sciences, sociology, and even Marxist analysis, using tools of critique to understand structural sin and injustice.

This context produced a Jesus deeply involved with the poor, the oppressed, and the politically marginalized, emphasizing liberation as a holistic, present reality, not solely a postmortem promise.

Key Tenets of Liberation Theology

- Option for the Poor

- Jesus consistently prioritized society’s marginalized: lepers, tax collectors, women, and children.

- Liberation theologians interpret this as a preferential option for the poor, insisting that any authentic Christian ethic must begin with solidarity with the oppressed.

- Jesus consistently prioritized society’s marginalized: lepers, tax collectors, women, and children.

- Base Communities

- These small, decentralized groups encouraged collective Bible reading, prayer, and social action.

- Scripture was interpreted through the lived experiences of participants, fostering empowerment and grassroots leadership.

- Base communities were often centers of education, advocacy, and local activism, merging faith with social praxis.

- These small, decentralized groups encouraged collective Bible reading, prayer, and social action.

- Martyrdom and Witness

- Figures like Oscar Romero, Archbishop of San Salvador, exemplified the movement’s commitment to justice.

- Romero’s public denouncement of human rights abuses and ultimate assassination in 1980 became a symbol of Christlike courage confronting oppressive regimes.

- Figures like Oscar Romero, Archbishop of San Salvador, exemplified the movement’s commitment to justice.

- Integration of Social Analysis

- Liberation theologians employ analytical tools drawn from economics, sociology, and political theory to identify systemic sin and structures of oppression.

- While some tools, such as Marxist critique, were controversial, they aimed to understand how institutional forces perpetuate injustice, not to replace spiritual truths.

- Liberation theologians employ analytical tools drawn from economics, sociology, and political theory to identify systemic sin and structures of oppression.

Critiques and Controversies

Liberation Theology has faced scrutiny from multiple angles:

- Vatican Concerns: In 1984, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith issued the Instruction on Certain Aspects of the “Theology of Liberation”, warning that some interpretations leaned too heavily on Marxist ideology and could compromise doctrinal orthodoxy.

- Political Tensions: Critics accused the movement of encouraging political rebellion or aligning too closely with revolutionary movements.

- Internal Debates: Some theologians worried that overemphasis on social action might overshadow spiritual formation and personal conversion.

Despite critiques, proponents argue that Liberation Theology’s ethics of action and commitment to the poor are faithful reflections of Jesus’ own ministry.

Jesus at the Center

Liberation Theology portrays Jesus in profoundly human and relational terms:

- A Jesus of solidarity: He walks alongside the poor, identifies with their suffering, and challenges the powerful.

- A Jesus of prophetic confrontation: He rebukes unjust authorities, cleanses the temple, and prioritizes God’s justice over social norms.

- A Jesus of hope: He offers both spiritual and material liberation, envisioning a world transformed by justice, mercy, and peace.

This vision aligns with Luke 4:18-19, where Jesus declares:

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor…to set at liberty those who are oppressed.”

For liberation theologians, this passage is not merely historical but prescriptive, guiding believers to enact justice in contemporary contexts.

Modern Impact

- Global Influence: While rooted in Latin America, the principles of Liberation Theology have inspired movements worldwide, including African, Asian, and urban North American communities.

- Social Engagement: Churches adopting these principles engage in community development, education, and advocacy, translating faith into tangible societal transformation.

- Cultural Resonance: Liberation Theology also influences art, literature, and music, portraying Jesus as intimately involved with human struggle and societal change.

Why This Matters Today

- Faith Meets Action: Liberation Theology reminds believers that spiritual devotion cannot be divorced from justice and compassion.

- Ethical Challenge: It confronts religious institutions and individuals to consider their role in systems of oppression and inequality.

- Theological Reflection: By re-centering Jesus in the context of the marginalized, it highlights the Gospel’s radical social dimensions, encouraging a holistic understanding of salvation.

Conclusion

Liberation Theology presents a vision of Jesus that is radically engaged, socially conscious, and ethically demanding. He is not an abstract Savior, distant from human suffering, but one who walks with the poor, confronts injustice, and inspires courageous action. From base communities to global movements, this Christ remains relevant, challenging believers to live faith through justice, mercy, and solidarity.

In a world marked by inequality and oppression, the Liberation Theology Jesus reminds us that the Gospel is not just about personal salvation but about transforming societies, reflecting the Kingdom of God here and now—through work boots as much as prayers.